Some discoveries happen by accident—a dusty barrel in a forgotten corner, a casual conversation about heritage, and suddenly, history reveals itself. That’s precisely what occurred when The Secret Sherry Society visited González Byass in Jerez de la Frontera for an interview with Silvia Flores, third-generation winemaker and future masterblender of this iconic house.

The Accidental Discovery

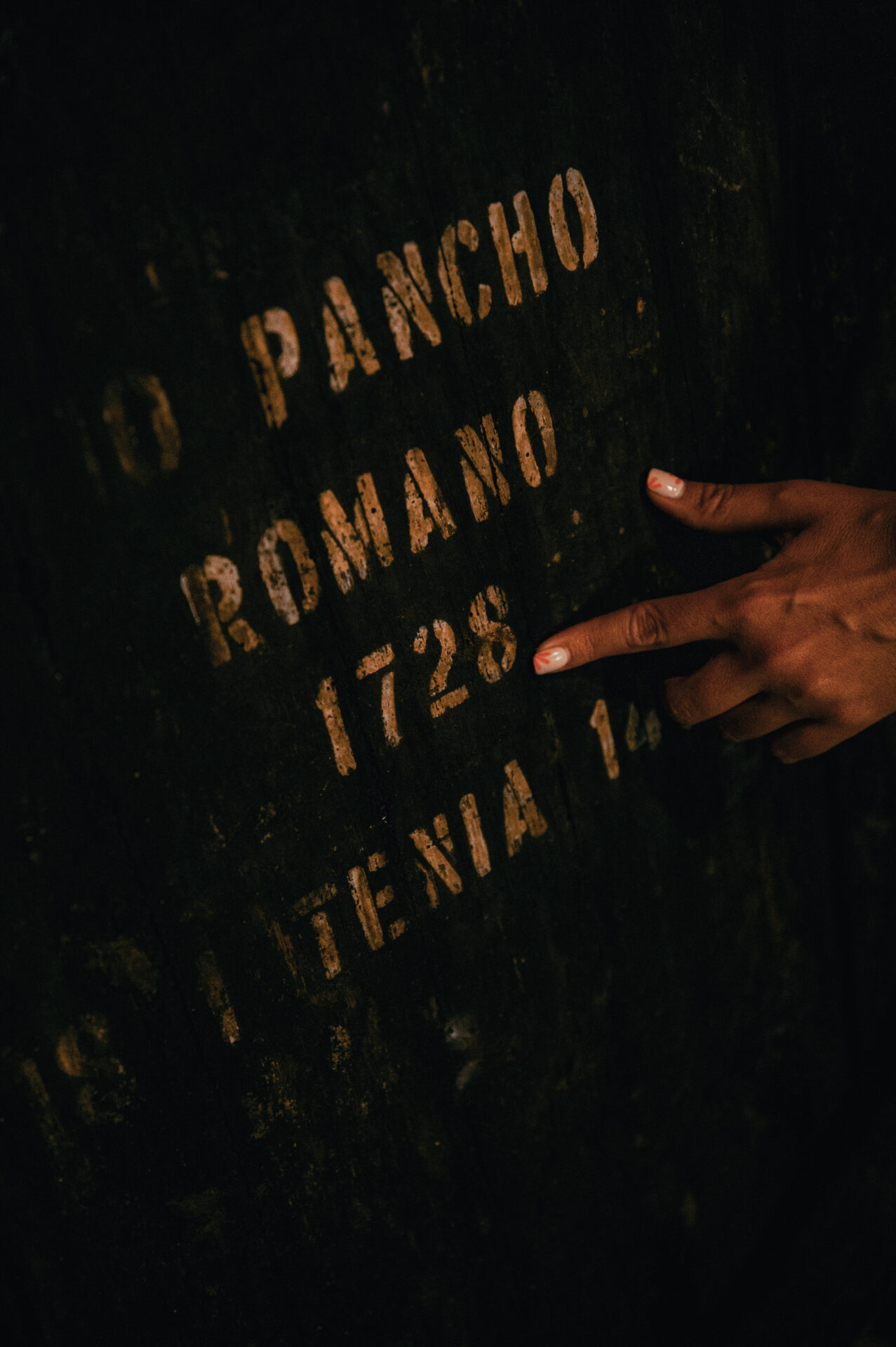

During their conversation about time and the magic of old Sherries, Flores mentioned something intriguing: somewhere deep in the bodega stood a mysterious barrel nobody could accurately date. After some detective work deciphering the weathered inscriptions, the puzzle pieces fell into place. The barrel had been purchased in 1871, but the wine inside was already 143 years old at that time. The math is staggering—this liquid time capsule dates back to 1728, making it nearly 300 years old.

To put that in perspective, this Sherry predates Mozart, Napoleon, Beethoven, and the American Declaration of Independence. It has survived the French Revolution, the Industrial Revolution, and both World Wars. Every drop tells a story that spans three centuries.

What Three Centuries Look Like in a Glass

When the barrel was finally opened after almost 300 years, the moment was historic. The wine had undergone an extraordinary transformation through oxidation—the natural exposure to oxygen that fundamentally changes a wine’s character—and the “angel’s share,” the poetic term for the gradual evaporation that occurs during aging.

The result? A wine of almost incomprehensible intensity. The color is deep, dark, nearly syrupy black. The texture resembles liquid amber, thick and viscous. Poured into three small copitas (traditional Sherry glasses), the aroma presents a labyrinth of nuts, spices, dried figs, wood, coffee, and leather—so complex it’s nearly impossible to comprehend fully.

Flores describes the taste as “incredibly concentrated, with a balance between acidity and sweetness that’s almost inexplicable after 300 years.” The wine is believed to be either Pedro Ximénez or Moscatel—both sweet Sherry varieties—though this remains uncertain, which is the first critical flaw in this discovery. Without knowing the exact grape variety, we’re missing a crucial piece of the puzzle that could help us understand how this wine achieved such remarkable longevity.

Breaking Records by Half a Century

Until now, the oldest known Sherry was produced in 1775 by Massandra in Crimea. A single bottle sold at Sotheby’s in 2001 for $43,500. When another buyer inquired, they were reportedly quoted $1 million—an offer they politely declined. More recent old Sherries, like Barbadillo’s Versos 1891 series (just over 130 years old), now sell for more than €10,000 per bottle.

This 1728 discovery shatters the previous record by nearly 50 years. It’s not just breaking records—it’s rewriting wine history entirely, potentially earning a place in the Guinness Book of World Records.

The Preservation Dilemma

Here’s the second critical issue: what happens now? The Secret Sherry Society calls this “world heritage,” not merely wine. They’re consulting with the Flores family about how to protect, document, and potentially share this treasure. But “potentially” is the key word—there’s currently no clear plan for public access or tasting.

This raises uncomfortable questions. Is keeping this wine locked away truly honoring it, or does world heritage deserve to be experienced, even if only by a select few? The tension between preservation and sharing remains unresolved, and this ambiguity feels like a missed opportunity to celebrate this discovery fully.

History in Liquid Form

Despite these concerns, this accidental discovery reminds us that patience, craftsmanship, and the right conditions can create something truly unprecedented. As Karel Klosse of The Secret Sherry Society notes, “This is a time machine in a glass, proof that when everything aligns, wine transcends its humble origins to become something immortal.”

The question now isn’t just what we’ve found, but what we’re willing to do to preserve it—and whether keeping history locked away honors it more than sharing it ever could.

More information: http://www.thesecretsherrysociety.com/

Foto credits: Nicky Regelink